What's Wrong and What To Do About It?

Let me start with an extended quote from “Why I Feel Bad for the Pepper-Spraying Policeman, Lt. John Pike“:

They are described in one July 2011 paper by sociologist Patrick Gillham called, “Securitizing America.” During the 1960s, police used what was called “escalated force” to stop protesters.

“Police sought to maintain law and order often trampling on protesters’ First Amendment rights, and frequently resorted to mass and unprovoked arrests and the overwhelming and indiscriminate use of force,” Gillham writes and TV footage from the time attests. This was the water cannon stage of police response to protest.

But by the 1970s, that version of crowd control had given rise to all sorts of problems and various departments went in “search for an alternative approach.” What they landed on was a paradigm called “negotiated management.” Police forces, by and large, cooperated with protesters who were willing to give major concessions on when and where they’d march or demonstrate. “Police used as little force as necessary to protect people and property and used arrests only symbolically at the request of activists or as a last resort and only against those breaking the law,” Gillham writes.

That relatively cozy relationship between police and protesters was an uneasy compromise that was often tested by small groups of “transgressive” protesters who refused to cooperate with authorities. They often used decentralized leadership structures that were difficult to infiltrate, co-opt, or even talk with. Still, they seemed like small potatoes.

Then came the massive and much-disputed 1999 WTO protests. Negotiated management was seen to have totally failed and it cost the police chief his job and helped knock the mayor from office. “It can be reasonably argued that these protests, and the experiences of the Seattle Police Department in trying to manage them, have had a more profound effect on modern policing than any other single event prior to 9/11,” former Chicago police officer and Western Illinois professor Todd Lough argued [link to http://www.wiu.edu/cacj/research/WJCJ/Spring%202010/Article%20Lough.doc no longer works].

Former Seattle police chief Norm Stamper gives his perspective in “Paramilitary Policing From Seattle to Occupy Wall Street“:

“We have to clear the intersection,” said the field commander. “We have to clear the intersection,” the operations commander agreed, from his bunker in the Public Safety Building. Standing alone on the edge of the crowd, I, the chief of police, said to myself, “We have to clear the intersection.”

Why?

Because of all the what-ifs. What if a fire breaks out in the Sheraton across the street? What if a woman goes into labor on the seventeenth floor of the hotel? What if a heart patient goes into cardiac arrest in the high-rise on the corner? What if there’s a stabbing, a shooting, a serious-injury traffic accident? How would an aid car, fire engine or police cruiser get through that sea of people? The cop in me supported the decision to clear the intersection. But the chief in me should have vetoed it. And he certainly should have forbidden the indiscriminate use of tear gas to accomplish it, no matter how many warnings we barked through the bullhorn.

My support for a militaristic solution caused all hell to break loose. Rocks, bottles and newspaper racks went flying. Windows were smashed, stores were looted, fires lighted; and more gas filled the streets, with some cops clearly overreacting, escalating and prolonging the conflict. The “Battle in Seattle,” as the WTO protests and their aftermath came to be known, was a huge setback—for the protesters, my cops, the community.

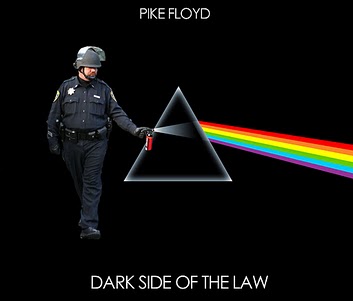

Product reviews on Amazon for the Defense Technology 56895 MK-9 Stream pepper spray are funny, as is the Pepper Spraying Cop Tumblr feed.

But we have a real problem here. It’s not the pepper spray that makes me want to cry, it’s how mutually-reinforcing up a set of interlocking systems have become. It’s the police thinking they can arrest peaceful people for protesting, or for taking video of them It’s a court system that’s turned “deference” into a spineless art, even when it’s Supreme Court justices getting shoved aside in their role as legal observers. It’s a political system where we can’t even agree to ban the TSA, or work out a non-arbitrary deal on cutting spending. It’s a set of corporatist best practices that allow the system to keep on churning along despite widespread revulsion.

So what do we do about it? Civil comments welcome. Venting welcome. Just keep it civil with respect to other commenters.

Image: Pike Floyd, by Kosso K

Not sure we can do anything, unless something sickening enough to be galvanizing takes place. You nail it in your “corporatist best practices” sentence. I can’t imagine what would be enough to act as the catalyst, since we apparently are fine with executive-ordered assassinations of U.S. citizens, with torture, with discarding the quaint and outmoded habeas corpus, and with claims that the founders had the National Association of Manufacturers in mind when they wrote the first amendment.