What Should FISA Look Like?

Jim Burrows is working to kick off a conversation about what good reform of US telecom law would be. He kicks it off with “What does it mean to “get FISA right”?” and also here.

To “get it right”, let me suggest that we need:

- One law that covers all spying

- Require warrants when the US spies on

- Anyone in the US

- US persons (citizens and resident aliens) anywhere

- Allow the intelligence agencies to spy freely on foreigners oversees, even if the taps are in the US

- Require Executive, Judicial and Congressional oversight when protected and unprotected communications are entangled.

- Criminalize violation of the Constitution.

I think we need a law which works cross medium, and addresses both content and routing information. It should lay out broad principles of privacy protection for Americans and people in America, and the times when spying is acceptable in ways that enable debate and discussion. We also need to address the very real abuses of past wiretapping statues, perhaps with increasing oversight as time goes by.

This is a hard area, and I encourage you to join in the discussion here, on Jim’s blogs, or on your own.

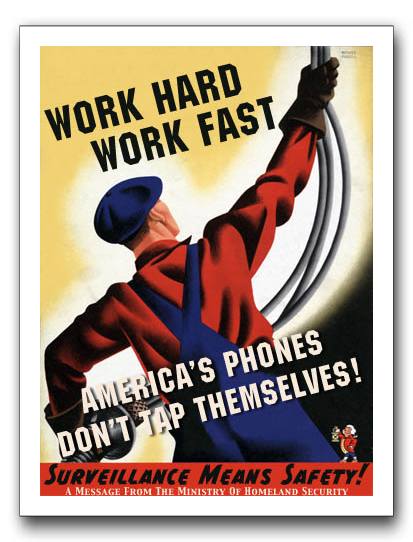

I hit post to soon, I’d meant to explain the image. I picked the image because I believe that listening to phone calls is sometimes something we should allow a government to do. If we do it right, it’s a valuable tool. If we do it wrong, it becomes an intrusion and a betrayal of our values. To date, we are doing it wrong, with secret courts rubber stamping requests under complex laws that few can understand. The result is that legitimate wiretapping is harder than it needs to be. Getting FISA right includes restoring public trust.

Image: Dr. Bulldog & Ronin.

I’m really pessimistic about the possibilities of getting this right.

The problem is oversight. They already claimed they were following #2 above, but leaks since have revealed that they aren’t. The problem is these programs are often secret by necessity, and it’s extremely difficult to create useful oversight of a secret program. Even if a person finds out they’ve been wronged, it’s usually impossible for them to take legal action. Without meaningful public oversight, it’s inevitable that any entity we create to attempt to put a check on this power will eventually become a captive of the agency it’s supposed to be overseeing.

What Brodbeck said.

I think it is fair to remark that any money spent in the last, say, 25 years on eavesdropping of this kind with any eye toward preventing damage to US interests by any state-level actor, and any terrorist in the senses of:

a) “islamofascist” nutcase, b) IRA or their ilk, or c) Red Brigade type morons would have been better spent grossly invading the privacy of anyone who worked on or near Wall Street, at least as far as preventing enormous damage to the country is concerned.

This is an enormous money sinkhole that, IMO, cannot do more good than harm.

David Brodbeck wrote:

I’ll quibble with your tenses at least a bit. They certainly weren’t following #2, and that was one of the reasons cited for passing the FISA amendments last year. My analysis (citation #3 in the bibliography of the article Adam pointed to above) suggests that that was in fact one of the areas specificly covered by the bill. The qustion is, has it succeeded. Are they still violating #2, now that all surveillance is covered by FISA and FISA specifically protects US persons? To date I have heard nothing to indicate one way or another.

I absolutely agree, and one of the places I think they fell down in the FISA amendments was in concentrating primarily on Congressional oversight, and underplaying judicial oversight. This underscores how the balances have broken down between the branches. Each trusts only themselves. A good law would insist on Judicial, Congressional, and executive oversight.

That’s part of the reasoning behind #5, and criminalizing Constitutional violations. It helps avoid the need to demonstrate standing to bring a civil suit. I don’t think this is enough, but it is part of the intent. Again, the law needs to be improved.

In the end, we can be pessimists and not bother to get better law on the books, surrendering to the paternalistic good intentions, if any, of the government, or push the legislature to fix the law, and to enforce it. My postings are an attempt to do the latter. One Senator–Feingold–has already declared his interest in seeing model legislation, and has said that if the Obama administration doesn’t do something in a few weeks, he will introduce legislation.

Let me bring up an example of a technical issue that I think the Congress can address without themselves having a deep understanding of the technology involved.

If I were to design a system to tap Internet email, extracting only communications that are between foreign persons located overseas (who are not protected by the Constitution), I would split the feed at major access points in the internet and run the full stream through filters that looked for information of interested contained in messages whose to and from addresses passed requirements of being identifiable as non-US persons located outside the US or specific people contained in my warrants database.

This would result in several types of data: Communications of interest that the gov’t has a right to (foreign or warranted), communications that the gov’t is known to no right to, and information of indeterminate type. Obviously interesting communications that is legitimate to tap should be turned over to a human.

But what is my system allowed to do with the rest? Must it discard or destroy it? Or would it be reasonable to take some of it and without letting any human see it, save it for later processing. If a warrant is added, for instance, or an address is alter found to be associated with someone for whom there was already a warrant, or an address is discovered to be outside the US, the historical data could be searched again and information of interest could be delivered to a human.

How about communications known to be between non-US persons located out of the US, but not recognized as being of any interest. Could it be kept for future rescanning? Could it be made available to humans to scan?

These questions determine how the code can be written and how information is stored, but are basically legal questions.